There’s something special I’d like to share with you today because very recently, life taught me another lesson about resentment. And that letting go of resentment is actually a lot easier than the mind makes us believe.

I’d like to share with you what I’ve learned, accompanied by a Stoic as well as a Buddhist perspective. If you’re harboring any form of resentment yourself, I’d recommend you to watch.

For those who think that the Einzelgänger is some kind of enlightened being, residing blissfully in eudaimonia somewhere in a forest shack, I have to disappoint you.

Although I do my best to improve my life everyday, and share as much as I can about what I’ve learned, I’m still quite a regular guy with the same flaws and imperfections as everyone else. No matter where you stand in life; what’s most important is that you make progress.

The Dutch have saying, which, in English, would go like this: pulling old cows out of the ditch. This saying includes a ditch and cows, probably because the Netherlands has many ditches and cows. But, what it means is ‘bringing up the past’.

Now, sometimes we have to bring up the past. We might need the past to solve things in the present or plan for the future. But bringing the past repeatedly and without good reasons, becomes a destructive habit. One thing that often keeps people stuck in the past, is resentment.

I’ve been grappling with feelings of resentment towards a few family members, which has anything to do with an ongoing family drama.

Although I’ve been able to let go of these feelings temporarily – especially of the experiences associated with this resentment – they just kept coming back. Sure, the Stoics say that we shouldn’t worry about things beyond our control, but in some cases, situations require more than simply ignoring them.

Resentment is something that we create ourselves because of the position we take towards things. It’s grown out of aversion. Slowly but surely we begin to create a story around this aversion; about the past, how people wronged us, and how they will wrong us in the future.

Like Epictetus said:

It is not events that disturb people, it is their judgments concerning them.

Epictetus, Enchiridion, 5

Being resentful, no matter how righteous, will not solve anything. It’s like drinking poison and waiting for the other person to die. And even when that person dies, you’re still poisoned. Thus, no good can come from walking around with a grudge as I have done.

The good thing about engaging on the philosophical journey as well as the practice of meditation is that I’ve gotten well aware of my feelings of resentment, what triggered them, and what exactly happened in my body because of them. This made it easier for me to let go eventually, and not be too bothered by them.

But, although I started to develop a more healthy detachment in regards to the whole situation, the resentment still came to the surface sometimes. Somehow, my ‘I don’t give a damn’ attitude wasn’t enough.

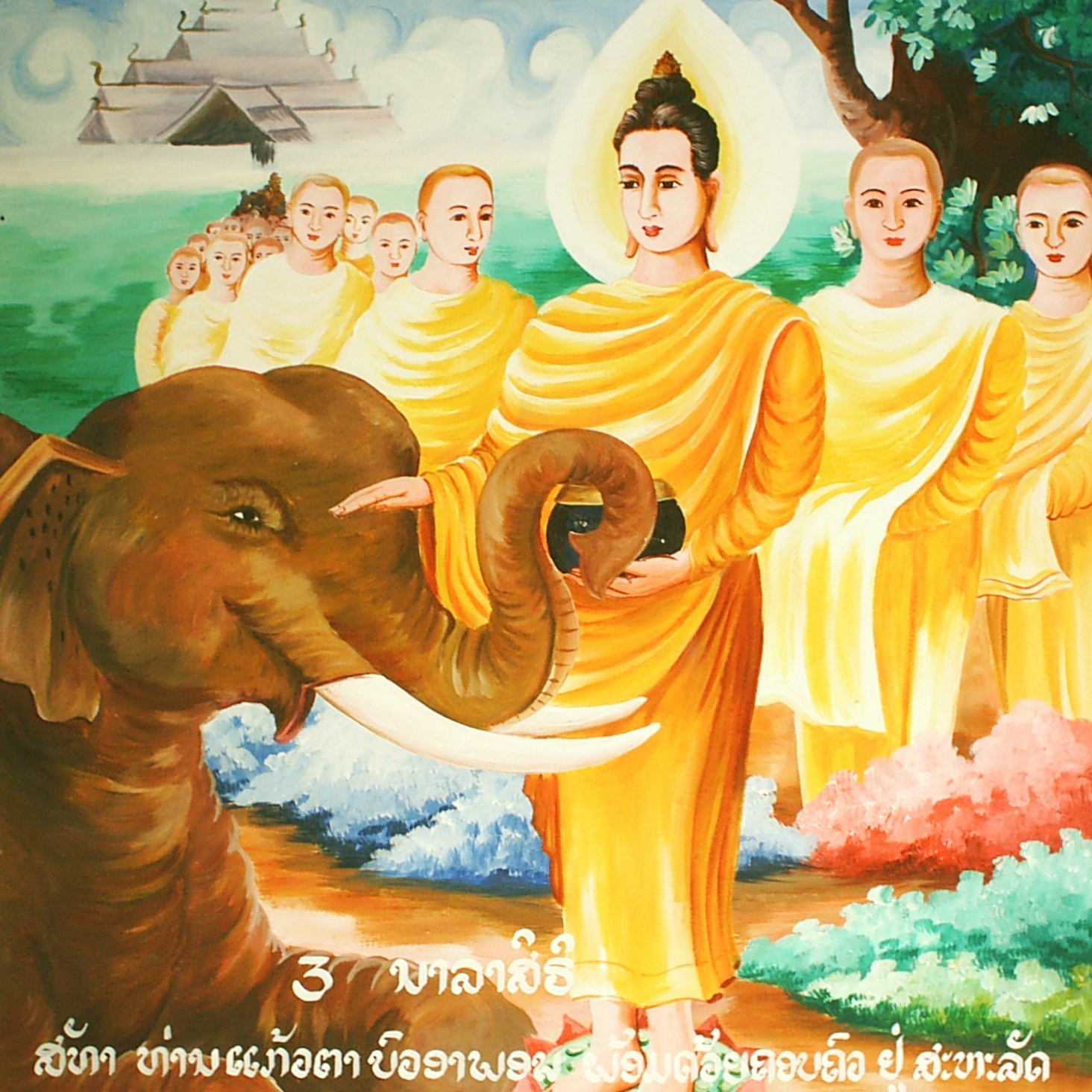

The Buddhists have a mind-hack that deals with resentment in a very effective and almost immediate way, which is called Metta. Also known as ‘loving-kindness’. Metta is the practice of loving all beings unconditionally.

Love eliminates the most destructive qualities of human life, like hostility, anger, and basically the whole range of aversion. By Metta, I started cultivating a sense of compassion towards my family members, which helped me greatly to let go of my resentment.

Letting go of resentment doesn’t have to mean that it completely disappears. Deep inside, resentment may still be there. But by letting go, we choose not to cling to it and not to follow it when it arises.

Still, I had the lingering thought that something had to be done. So, I starting examining my ethical structure. Although the Stoics and the Buddhists acknowledge the power of ‘letting go’ and ‘living in the moment’; they also encourage us to do the right thing.

The old Stoics were great apostles of justice. Looking at Stoic ethics we will realize that the true path to happiness isn’t a total disinterest towards the world, but rather, a life of virtue. The Buddhists have quite similar ethical views based on the idea that doing the right thing will, eventually, end your suffering and lead to enlightenment.

Many disputes, whether they are family issues or work-related, aren’t solved because of cowardice and tainted by unfair dealing. We’re afraid for confrontation, afraid to speak the truth, and, instead, we talk ill behind the backs of those we should confront. According to the Stoics, behaviors like these belong in the domain of vice. Vice leads to unhappiness.

So, doing the right thing means addressing unfairness and cowardice, which can be done by the virtuous opposites: fair dealing and courage. For me, this meant picking up the phone and speaking my mind.

Of course, when we take action, the outcome is uncertain. How other people respond is not up to us. But when we do the right thing, does the outcome really matter? At least we did the best we could – fueled by goodwill and free of resentment. That’s what matters.

Confrontation and trying to solve the situation isn’t always the right thing. In some cases, the best way is to simply let it go and let our attachments past events dissolve. This really depends on the situation, though. And, thus, doing the right things isn’t one-shoe-fits-all and requires a careful examination.

I believe, however, that this examination can only be done after we achieved a healthy detachment from the situation, so we can think clearly and without judgment or anger. Letting go of resentment was the first step into solving a lengthy impasse, in a way that benefits all parties involved.