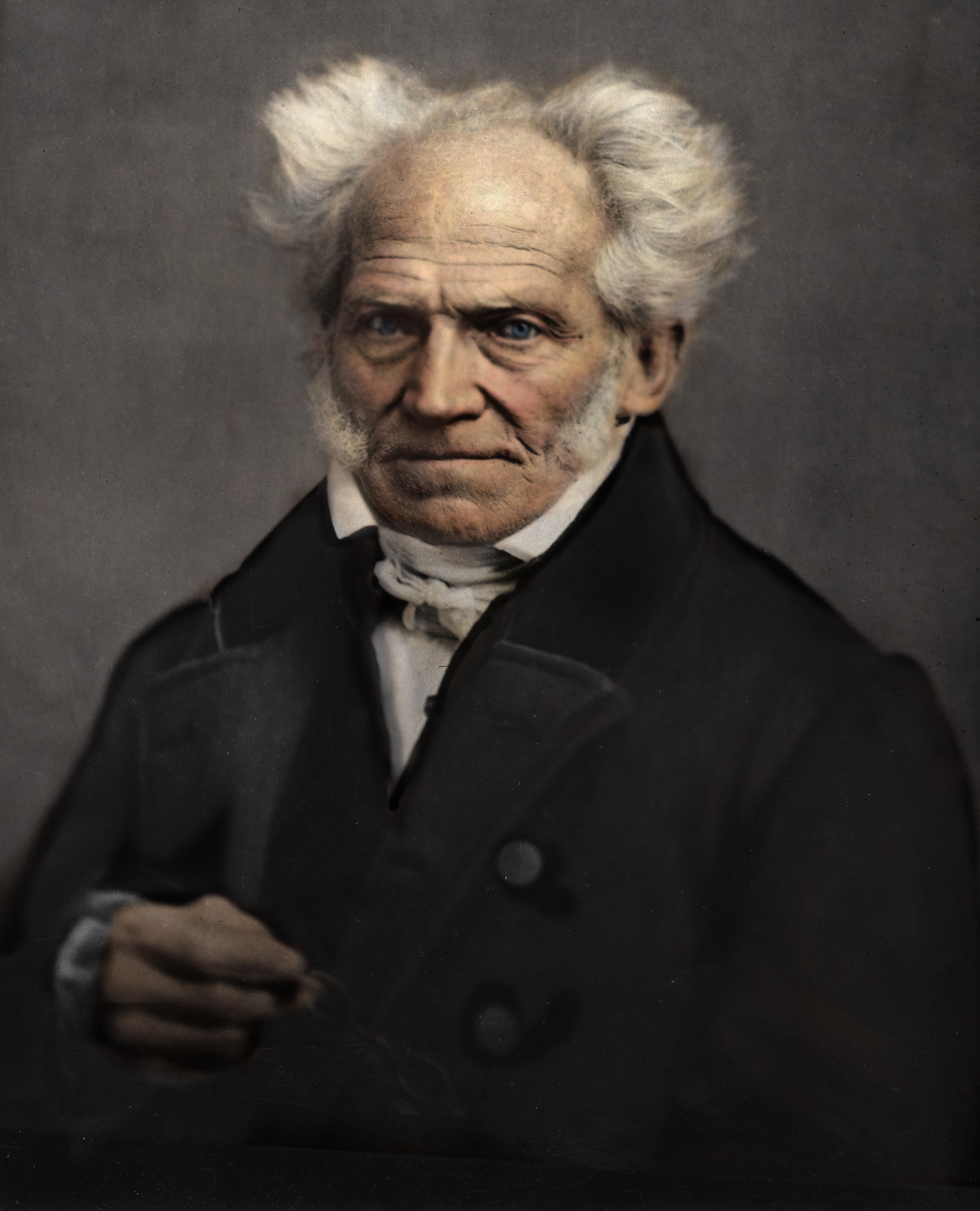

What if this world is actually one giant prison? When the 19th-century philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer observed the amount of pain that we experience during our lifetimes, he concluded that it’s not happiness and pleasure we’re after, but a reduction of the ongoing suffering that’s an inherent part of existence. When we compare this world to prison – or more specifically: a penitentiary – while looking through the grim lens of Schopenhauer’s philosophy, we’ll see that the similarities are astounding. As is the case with prison, no one (in general) chooses to be here, we can’t leave until our sentence ends or when we ‘end’ ourselves, we’re limited by the walls of the ever-fleeting present moment, and within the confines of our limitations, we generally experience a stream of suffering, tragedy, worry, and misery.

We desperately go from one pleasure to another just to experience temporary relief from pain. In the process, the organisms that inhabit the Earth, driven by what Schopenhauer called the will-to-live, feed on each other in an attempt to survive, just so they can prolong their miserable lives a bit longer. Like prison gangs, the species of the world are entangled in a continual war for dominance. “Eat or be eaten,” seems to be nature’s order when we look at how plants, as well as certain animals, only serve as food for other animals, which in turn succumb to the destructive presence of human beings. And humanity, in turn, while exploiting its own members, and draining its natural habitat of resources, falls prey to some kind of disease or disaster.

When we remove the veil of ignorance and behold the harsh reality we live in, we might start to question the idea that God has created this world out of, and I quote, “pure caprice, and because he enjoyed doing it, and should then have clapped his hands in praise of his own work.” End quote. No, Schopenhauer’s view of the world is one of agony – devoid of divine grace – as it has much more in common with a “penal colony” than with the creation of a benevolent deity. Now, seeing the world as a prison sounds like a recipe for personal misery. Why not adopt a more positive, more hopeful perspective? Why look at it with such pessimism?

Well, Schopenhauer’s idea comes with a twist. Within his pessimistic worldview lies a secret that could be very beneficial to humanity. Based on his essay On the Sufferings of the World, this video explores Schopenhauer’s pessimistic outlook on life and reveals his secret.

Life as a prison

Schopenhauer stated that (as opposed to what many people think) not pleasure but pain is the positive element of existence. He argued that evil is what makes its existence felt and is, therefore, positive. But good, on the other hand, is negative. The state of happiness and contentment is nothing more than a desire fulfilled or the end of some state of pain. So, the experience of pain is the source of our desires and needs. Hunger, for example, is a state of discomfort (which has the potency of becoming painful) that leads to us desiring food. Thus, eating is not a positive experience as it’s only considered pleasurable because it fulfills a desire that is derived from pain, or, a sense of lack.

According to Schopenhauer, pain far outweighs pleasure in this world. And the pleasure we incur is often less pleasurable than we expected, while the pain is much more painful. We only have to look at an animal who’s eating another animal, and compare the pleasure of eating with the pain of being eaten to decide which one of the two is more severe.

Schopenhauer not only calls life a disappointment, but also a cheat. Life, generally, becomes more painful when we age, as we experience tragedy after tragedy while we become increasingly prone to sickness and death. And even though life unfolds as a string of misfortunes, when we’re still young and idealistic the world looks so promising. But eventually, our high hopes erode and we end up disappointed and wretched by the hardships that have fallen upon us. We’re met with insecurity, loss, betrayal, physical pain, and possibly even mutilation. We then realize that life isn’t all rainbows and sunshine and that happily ever afters are few and far between, and that the dream house, the big fat savings account, or the interesting social circle are no consolation for the immeasurable pain that comes with being stuck on this desolate rock of doom called Earth. If anything, the fulfillment of all that we wish and the continual suppression of desire by the means of pleasure leads to boredom, which is just another form of dissatisfaction.

Schopenhauer’s view of the world leaves no room for optimism: life is a burden, “the result of some false step, some sin of which we are paying the penalty,” and it would have probably been better if it had never happened at all. I quote:

If you try to imagine, as nearly as you can, what an amount of misery, pain and suffering of every kind the sun shines upon in its course, you will admit that it would be much better if, on the earth as little as on the moon, the sun were able to call forth the phenomena of life; and if, here as there, the surface were still in a crystalline state.

Arthur Schopenhauer, On the Sufferings of the World

Schopenhauer compares us to lambs in a field under the eye of a butcher who decides who’s going to be the next prey. Powerless over our fate, we can only wait, imprisoned by life itself, for the moment that the next misfortune washes over us. Some choose to escape this cycle of misery by checking out early. Others proceed doing what they’ve always done, which is consoling themselves by the engagement in pleasure. And so we drink to forget about past sorrows and indulge in distractions to not be consumed by worries about the misfortunes yet to come. As prisoners, we sit out our penance and make it bearable at most by minimizing pain. Even though it sounds gloomy, it’s this reality that Schopenhauer wants us to embrace. I quote:

If you want a safe compass to guide you through life, and to banish all doubt as to the right way of looking at it, you cannot do better than accustom yourself to regard this world as a penitentiary, a sort of a penal colony…”

Arthur Schopenhauer, On the Sufferings of the World

In Schopenhauer’s view, it’s the very understanding and acceptance of the human predicament, no matter how bleak, that contains the key to a more compassionate mode of living.

Hello, fellow-sufferer

When we look around us, we see competition, lack of tolerance, and even hatred towards individuals and groups. So, life already being difficult enough doesn’t stop us from making it even more difficult for one another. We’ve become each other’s sources of misery instead of support. We are unforgiving towards other people’s evil deeds. We hate our enemies for inflicting pain upon us. We’re overly critical of those who make mistakes. But isn’t this animosity misplaced if, at the end of the day, the same tragic fate subjugates us all: being alive and human and part of a world that’s stacked against us and has an awful lot in common with a jailhouse? I quote:

They are the shortcomings of humanity, to which we belong; whose faults, one and all, we share; yes, even those very faults at which we now wax so indignant, merely because they have not yet appeared in ourselves. They are faults that do not lie on the surface. But they exist down there in the depths of our nature; and should anything call them forth, they will come and show themselves, just as we now see them in others.

Arthur Schopenhauer, On the Sufferings of the World

If we accept this view of life and acknowledge that we all share the same anxieties, insecurities, grief, physical pain, and restlessness because we’re part of the same miserable existence, we can regulate our expectations accordingly. Incidents that are usually looked upon as ‘bad,’ are nothing unusual or unexpected, but rather logical consequences of an existence based on misfortune. For example, when people are being rude to us, we can imagine how tormenting life has been to these individuals so far, and that their rudeness is to be expected, and that we shouldn’t take it so personally. They’re prisoners, just like us, waiting for the next beating by the guardsmen, and eventually their execution. So, unless they’ve managed to transcend the suffering that comes with life, it’s understandable that people aren’t always on their best behavior.

Along with acceptance, Schopenhauer points out that his pessimistic outlook creates an opportunity for compassion. This is the secret. Compassion is the ability to muster sympathy and concern towards the sufferings or misfortunes of other people. Taking the amount of misfortune that life brings into account, and the fact that no one has ever chosen to be here, we can safely say that compassion is the answer to anyone who partakes in it. Moreover, Schopenhauer thought that we owe compassion to our fellow human beings, as it’s so essential for our well-being. From compassion flows our willingness to help each other out, our ability to accept another person’s imperfections, our inclination to make this collective prison sentence more bearable, because we’ve chosen to alter the way we see each other: not as enemies, but as, how Schopenhauer called it, “fellow-sufferers.”

This may perhaps sound strange, but it is in keeping with the facts; it puts others in a right light; and it reminds us of that which is after all the most necessary thing in life—the tolerance, patience, regard, and love of neighbor, of which everyone stands in need, and which, therefore, every man owes to his fellow.

Arthur Schopenhauer, On the Sufferings of the World

Thank you for watching.