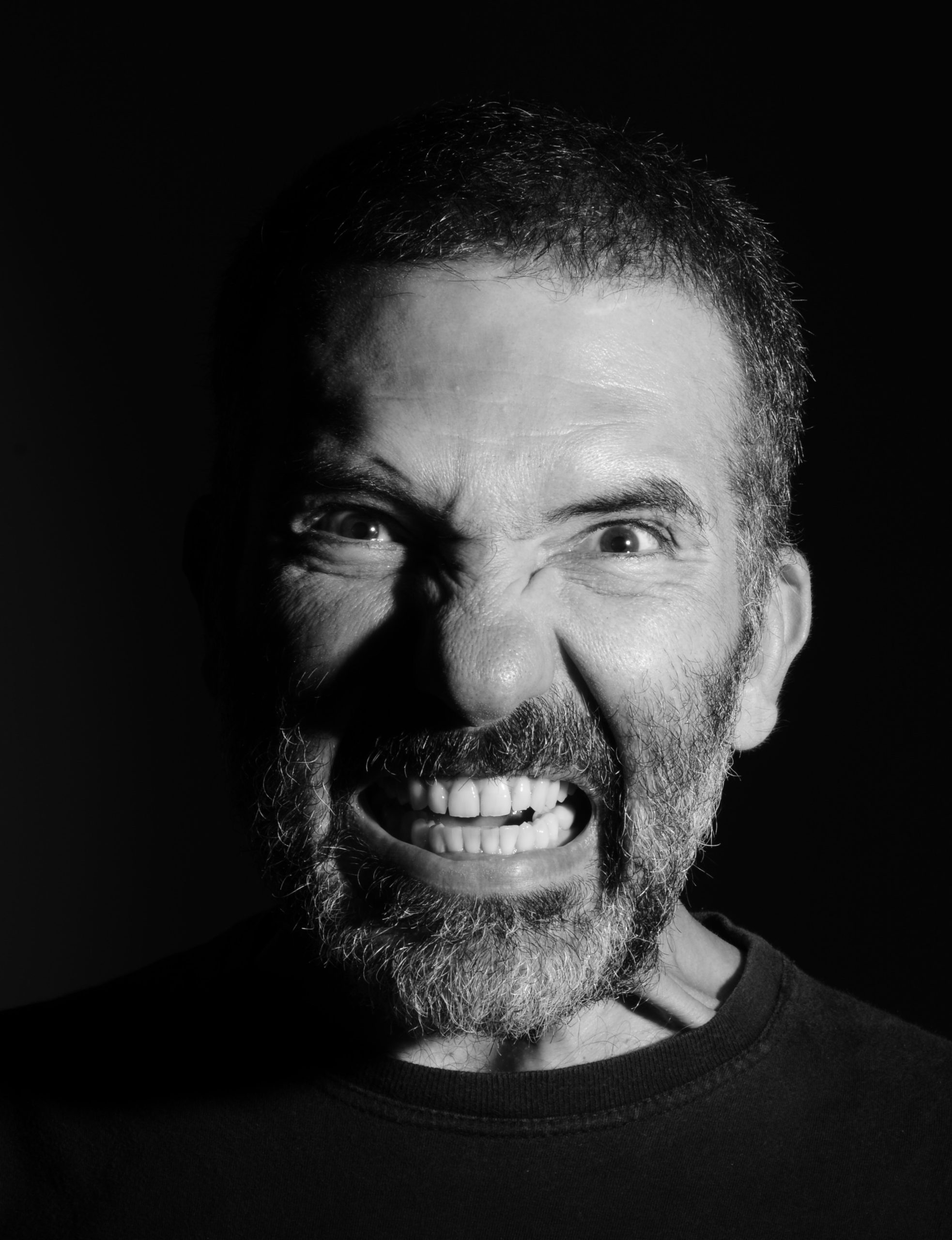

Feelings of bitterness and revenge are like heavy stones we carry around on our backs. And if we’re unable or unwilling to throw these stones onto the ground and walk away from them, we’ll not only exhaust ourselves; the load also increases because of new hurtful life experiences. Eventually, we’ll carry even more stones until we can’t handle the weight anymore and collapse. Resentment hurts. It can eat us up from the inside. Somehow we believe that the only way to rid ourselves of resentment is when some form of retaliation occurs. But this may never happen. And so, we run the risk of spending the majority of our lives suffering past hurts while our enemies flourish.

As Viktor Frankl wisely stated: “When we are no longer able to change a situation we are challenged to change ourselves.” End quote. We can’t change the past, and we can’t change others. Our mental well-being doesn’t depend on whether or not we get revenge or receive an apology. It depends on how we handle the pain inflicted on us. So, we have a choice. We can choose to stay attached to old hurts and take our suffering into the grave. Or we can choose to take the antidote and let go of our suffering, so we spend the rest of our lives without the heavy burden of resentment. This antidote has a name: forgiveness. This article explores five healthy ways to forgive and let go, based on philosophy and psychology.

First of all, it’s probably important to mention that forgiveness does not equate with forgetfulness. We can forgive someone without forgetting what this person has done. If we’d also forget or – perhaps more common – refuse to see the reality of a person or situation, we open ourselves up to being hurt again. Therefore, the best option in some cases might be to forgive someone without ever associating with this person again for the sake of self-protection. The Buddha advised not to associate with the foolish, including (quote-unquote) “fools” with unwholesome intentions.

Accepting that humans are flawed

“Expectations are premeditated resentments,” wrote Allen Berger, author of several books about addiction and recovery. Berger pointed out that we often blame other people for our problems, but that in reality, the cause of our suffering doesn’t lie with these people, but with our expectations of them. Resentment often stems from expectations not being met and the disappointment this leads to. One of our biggest mistakes is expecting others not to make mistakes; how ironic this may sound.

We sometimes put people on a pedestal, projecting all kinds of expectations onto them. For example, we expect a partner always to be caring and interested in what we have to say. Or we expect a friend always to be helpful and willing to listen. But by doing so, we don’t see them for the imperfect human beings they are, but as fantasies of them that we’ve created in our minds. We often see these fantasies with parents and children. Many parents have high expectations of their children, and vice versa: children expect their parents to be good parents. But these fantasies rarely resemble reality. Stoic philosopher Epictetus commented on the phenomenon of having a “bad” father, saying:

Is you naturally entitled, then, to a good father? No, only to a father.

Epictetus, Enchiridion, 30

And thus, from a Stoic point of view, not people’s behavior causes resentment but our expectations of them. People are inherently flawed. They make mistakes, gossip, betray, lie, and violate our boundaries. Even people we’ve held in such high regard may end up disappointing us. Accepting this can make it easier for us to let go of our resentment. Why be angry about a reality we can’t control?

Contemplating anger and resentment

The Buddha distinguished three basic causes of suffering: greed, ignorance, and hatred. He described hatred as a great stain on the personality because of its destructive nature. We only have to contemplate the terrible things that have happened due to hatred: people getting wounded or killed, bloody wars, genocide. Hatred is devastating on the inside too. Holding on to resentment is like holding hot coals and waiting for the other to get burned. Despite all the revenge fantasies we conjure in our minds (but never carry out), having a grudge often hurts ourselves the most.

We can be mad at the world, at ourselves. We can feel bitter about the unfairness of life or about the things people around us said and did. But no matter how much oil we throw on the flames of our disgruntled minds, we cannot change what happened, nor can we control the universe. We can keep drinking poison, waiting for our enemies to die, but it’s us who die a painful death in the end. By contemplating the devastating nature of anger and resentment within ourselves and the outside world, we can remind ourselves that it’s unwise to let such emotions poise our minds. Therefore, by letting go of these emotions by forgiveness, we stop watering the seeds of destructiveness. It’s a win-win situation.

Being mindful of destructive thinking

For some people, forgiveness is as simple as making a decision and moving on. But for most of us, the act of forgiveness doesn’t seem so easy. Resentment is stubborn, and despite any resolution we make, negative thoughts and emotions can appear again and take over our mental state. And before we know it, the grudge towards the person we previously forgave is back in full force. Stoic philosopher Seneca was aware of this phenomenon. In his essay Of Anger, he noticed that we have a say in controlling our anger, and we should get rid of it when we encounter it.

A large part of mankind manufactures their own grievances either by entertaining unfounded suspicions or by exaggerating trifles. Anger often comes to us, but we often go to it. It ought never to be sent for: even when it falls in our way it ought to be flung aside.

Lucius Annaeus Seneca, Of Anger, 3-12

The Buddhists are aware of this phenomenon too, and thus stay mindful to let go of unwholesome thoughts before they grow and spread like cancer. The latter happens when we hold on to certain memories, fantasies, narratives, or fears about the future. We could see our minds as a garden, and it’s our job to tend it. We can let bad weeds spoil it, or we can uproot them, throw them out, and prevent new ones from entering. But, to be skillful gardeners, we need to be mindful. The Buddhists propose meditation as the method to train the mindfulness muscle. Thus, the decision to forgive is the first step. But the next step is keeping our mental faculties clean by removing and avoiding junk that revokes resentment towards the person we have forgiven. Forgiveness is useless if we can’t commit to it.

Not forgetting the positive

Nature has programmed us in such a way that we’re more susceptible to negativity than to positivity. This is why many people look in the mirror and mainly see their undesirable aspects. We call this phenomenon the brain’s “negativity bias,” and it’s causing us to see fault rather than merit in those around us. Hara Estroff Marano, editor at large at Psychology Today, writes the following on the origins of the negativity bias, and I quote:

Our capacity to weigh negative input so heavily most likely evolved for a good reason—to keep us out of harm’s way. From the dawn of human history, our very survival depended on our skill at dodging danger. The brain developed systems that would make it unavoidable for us not to notice danger and thus, hopefully, respond to it.

Hara Estroff Marano, Our Brain’s Negative Bias, Psychology Today

Nature’s instruments for survival can be a Godsent until they begin to affect us in destructive ways. Someone’s negative characteristics can cloud their favorable traits to such an extent that we cannot see the positive anymore. In our biased minds, this person has become purely evil. It’s pretty difficult not to feel repulsed by someone who doesn’t have any positive traits – let alone forgive them. So, we might want to look beyond the vast specter of negativity and see that the people we resent are also carrying good within them and that it’s human to possess both evil and good. When people give us hell, we often grow more robust, more insightful, and more compassionate. Past hurt, no matter how severe, may just be a blessing in disguise.

Choosing love, not hate

There is this tendency among many people to answer hate with hate. But we see that this mostly makes matters worse and often results in violent conflicts and bloodshed. Activist and Baptist minister Martin Luther King Jr. decided to stick to love, as hate, according to him, is too great a burden to bear. He argued that violence is a descending spiral that brings about precisely the thing it seeks to destroy:

Through violence, you may murder the liar, but you cannot murder the lie, nor establish the truth. Through violence, you murder the hater, but you do not murder hate. In fact, violence merely increases hate. Returning violence for violence multiplies violence, adding deeper darkness to a night already devoid of stars. Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that.

Martin Luther King Jr.

Love doesn’t necessarily mean that we should engage with people. We can love from a safe distance, wishing them the best, without getting burned by their flames of malice. Even though the people that hurt us seem resistant to our love and keep giving us poison, choosing “love” over “hate” is still the best option for our own mental well-being. Forgiveness fueled by love melts away our resentment and anger and replaces them with compassion. Compassion is a force that doesn’t destroy but empowers; that doesn’t hatefully antagonize but calmy recognizes the humanity in every person (despite their flaws). Compassion may not necessarily drive hate out of others, but it definitely drives it out of ourselves.

Thank you for watching.